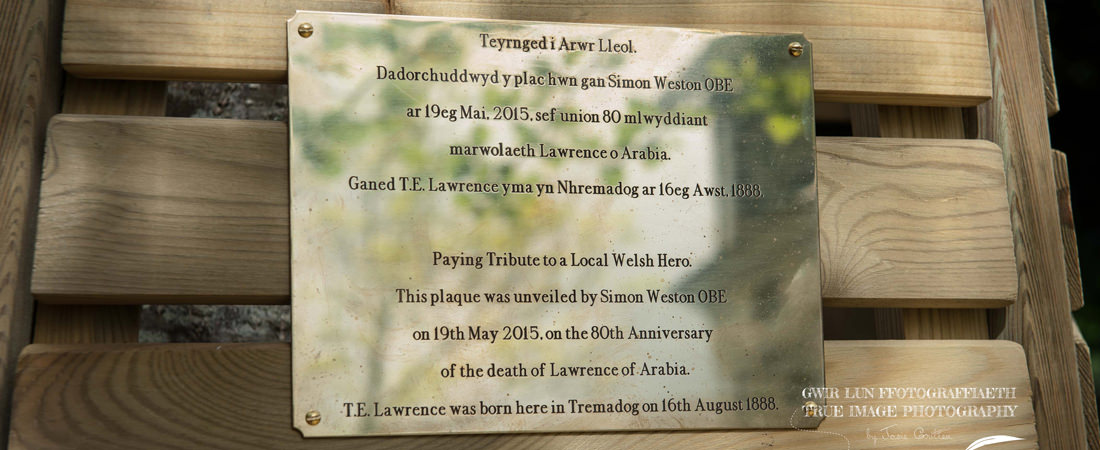

1888, 16th August: Thomas Edward Lawrence, is born at Tŷ Lawrence, in Tremadog North Wales. Also know as Snowdon Lodge, Tŷ Lawrence ( the House of Lawrence) is the birthplace of Lawrence of Arabia. Here begins the life of Lawrence of Arabia.

1896: The Lawrence family moves to Oxford.

1907-1910: T.E Lawrence studies at Jesus College, Oxford. For his thesis on crusader castles he cycles 2,400 miles through France and walks 1,100 miles in Syria.

1911: Lawrence starts work as an archaeologist at Carchemish in Syria.

1914: War begins. Lawrence is sent to Cairo.

1915: T.E Lawrence’s two brothers, Will and Frank, die in France.

1916: The Arab Revolt begins and Lawrence joins Sheriff Faisal in his campaigns against the Turkish people.

1918: Damascus is captured from the Turks. Lawrence returns to England.

1919: The Paris Peace Conference dashes Arab dreams of independence.

1921-1922: T.E Lawrence, working with Churchill at the Colonial Office, helps to achieve some degree of Arab self-rule.

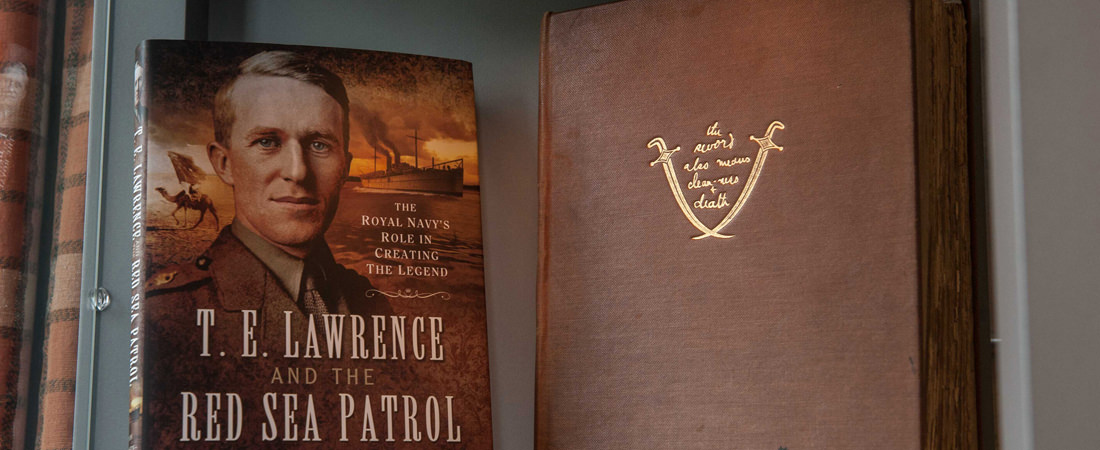

1922-1935: Lawrence first joins the Royal Air Force under the pseudonym of J.H. Ross, but disclosures in the press cause his discharge. He serves in the Tank Corps, then rejoins the RAF as T.E. Shaw. During this period he publishes Seven Pillars of Wisdom, The Mint and his translations of Le Corbeau’s Gigantesque and Homer’s Odyssey.

1935, 13th May: T.E. Lawrence was critically injured while driving his motorcycle through the Dorset countryside. They say he had swerved to avoid two boys on bicycles. 19th May: Lawrence dies as a result of a motorcycle accident near his home in Dorset.

Thanks to the T.E Lawrence Society for the facts above about the Life of Lawrence of Arabia. You can find out more about the active T.E Lawrence Society here.

Exert about the Life of Lawrence of Arabia from Lawrence of Arabia, a Pocket Biography by Jeremy Wilson (Stroud, Sutton Publishing, 1997)

The Life of Lawrence of Arabia became famous after the First World War because of the remarkable role he had played while serving as a British liaison officer during the Arab Revolt of 1916-18. When the war ended, an American journalist, Lowell Thomas, toured Britain and the Empire giving an outstandingly successful slide-show about Lawrence’s achievements. The romantic story of Lawrence’s campaigns in Arabia and Allenby’s in the Holy Land appealed strongly to a British public sated with horrific accounts of trench warfare on the Western Front. From this beginning grew the legend of ‘Lawrence of Arabia’.

Thereafter, the facts of Lawrence’s war-adventures were often obscured by myth. Even today, his reputation is a favourite target for popular controversialists. Nevertheless, when the secret British archives of the Middle East campaigns were finally released in the 1960s and ’70s, they showed that Lawrence’s service with the Arabs had been no less remarkable than the legend. Lawrence himself had little wish to be remembered as a war hero: he could hardly bear to think about his wartime role. His enduring ambition was to be a writer. He once confessed his hope that, “in the distant future, if the distant future deigns to consider my insignificance, I shall be appraised rather as a man of letters than a man of action.”

His literary reputation rests on a body of writing which is almost entirely autobiographical. It includes at least 6,000 letters written between 1906 and his death in 1935, and two autobiographical books. The first, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, is an account of his service with the Arab Revolt. The second, The Mint, is centred on his experiences as an anonymous recruit in the ranks of the RAF. It was there, to the astonishment and distress of many contemporaries, that he chose to spend his life after 1922.

Both in his books and letters, Lawrence was an acute observer of people, places, and events. Among the most memorable passages in Seven Pillars are the vivid descriptions of desert landscapes and of the Bedouin irregulars whose life he shared. The Mint, written in a very different style to Seven Pillars, is, like Solzenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a work of observation written by a highly intelligent man who found himself effectively imprisoned. Lawrence distilled its spare descriptions from events that he had witnessed over and over again. Both Seven Pillars and The Mint have for many years ranked among Penguin’s modern ‘Classics’ Lawrence’s letters are no less remarkable. His friendships ranged from fellow-servicemen in the ranks to leading figures in the worlds of literature, art, and politics. In many cases, letters were almost the only vehicle for these relationships, since the circumstances of his life meant that he could rarely meet his friends.

Should he be appraised as a writer or a man of action? At the close of the twentieth century the verdict remains open. Other men of action marked history more deeply; other writers earned higher acclaim; yet few of his contemporaries combined both practical and intellectual achievements to the degree that Lawrence did. That intriguing combination has helped to sustain the public’s fascination with his life, as has the deeply introspective personality revealed in his writings.

From Lawrence of Arabia, a Pocket Biography by Jeremy Wilson (Stroud, Sutton Publishing, 1997)